Every app consists of different flows for achieving a specific goal. For example, there is a sequence of views for sign up. When sign up flow ends, we need to move to so called main view what represents the main functionality of the app. There are definitely a lot of different ways how to handle app navigation and each of the approach have their own pros and cons. With this in mind, the approach I am going to demonstrate this time, is how to use flow controllers and using responder chain to connect flows to each other.

Navigating from flow to flow

Flow controller is a UIResponder coordinating a single flow in an app. It handles showing views, injecting dependencies and storing intermediate values required to pass from one view controller to another. Navigation from one flow to another happens using responder chain. This also enables us to use sending actions to nil first responder in story boards and xib files. Using responder chain adds extra flexibility when restructuring an app or changing flows a lot. There is only a little code needed to set up new flows. It is a kind of lightweight approach to coordinator pattern where delegation is replaced with responder chain.

Setting up protocols

As a first step we define two protocols: one for defining entry points and the second one for accessing flow controllers from any responder in responder chain. Flow controllers are going to conform to specialised presenting protocol and responders (typically view controller), which trigger navigation, conform to one of the controlling protocols. FlowPresenting protocol is going to define a single function what is used for presenting a first view in the flow. I find examples to be the best way of learning new approaches, therefore let’s build a sample app with three flows: app, login and main flow.

Controlling app flow

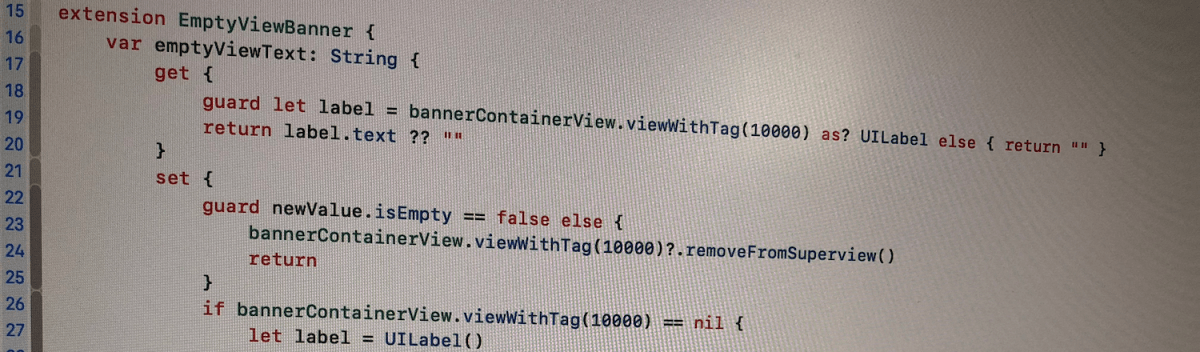

AppFlowController is the controller handling presenting new flows. It conforms to AppFlowPresenting protocol what defines entry points to all the different flows. In addition, it handles inserting active flow to responder chain which enables easy access to flow controller from any presented view controller. Finding a flow controller from responder chain is implemented using a generic function. This enables implementing new getters for other flow controllers with just one line.

In the current sample app, AppFlowController is going to handle representing all of the flows in the app. This is because all the current flows are consisting of one branch in a so called tree of flows. If we would have a more complex application, other flow controllers would handle their own subset of flows and would insert those flows into responder chain (like AppFlowController is inserting LoginFlowController and MainFlowController into responder chain). This kind of architecture allows creating a tree like structure of flows and separating them from each other – there is not going to be a single controller handling all the flows.

In the example app we do not use storyboard for initialising the first view (“Main Interface” field in target settings is empty). Instead, we set up a window ourself and use AppFlowController for presenting the first view. In addition, we inject a manager storing a set of dependencies view controllers might require. Having approach like this, we do not need singletons and instead, flow controllers insert dependencies into view controllers. Using dependency injection keeps the overall dependency graph nice and clean.

Creating login flow controller

LoginFlowController has similar set up as AppFlowController with exception of not inserting a subsequent flow into responder chain. In the sample app, login flow does not branch into several other login related flows. At the end of login flow, AppFlowController is used to present main content view. Due to generic function we added to UIResponder extension, login flow controller accessor consists of a single line.

Let’s see how view controllers in the login flow trigger navigation. LoginViewController conforms to LoginFlowControlling. This makes loginFlowController accessor available and we can use it for triggering navigation. It should be noted that loginFlowController accessor returns an object conforming to LoginFlowPresenting and does not explicitly declare the type of LoginFlowController. This means that LoginViewController does not know about LoginFlowController, instead, it just knows that the returned object implements methods listed in LoginFlowPresenting protocol. Less coupling makes it easier to test and restructure app in the future.

Another important point to note here is that it is so easy to add navigation capability to any other view controller. Flow controller does not need to be injected and in the end, we just need to make two changes in the whole view controller – protocol extension takes care of adding getter to the interface and triggering navigation is just a single line of code.

Navigating from login to main view

AccountDetailsViewController is the last view controller in the login flow and it should trigger navigation to the main flow. As seen in previous paragraph, triggering navigation requires only two changes. This is also the case here.

Summary

This time we took a look on how to use flow controllers and responder chain to easily manage navigation from one view to another. In the end we implemented a scalable architecture where adding navigation trigger points just require a few changes. Scalability comes from the fact that flows can be arranged into tree like structure and there is no requirement to have a single object managing all the flows. Moreover, we added a dependency injection capability to flow controllers which make it so much easier to test components separately and not worrying about singletons.

If this was helpful, please let me know on Mastodon@toomasvahter or Twitter @toomasvahter. Feel free to subscribe to RSS feed. Thank you for reading.

Example Project

FlowController (GitHub) Xcode 10.1, Swift 4.2.1

References

Using Responders and the Responder Chain to Handle Events (Apple)

Generics (Swift)

Tree (data structure) (Wikipedia)