SKWarpGeometryGrid is a grid based deformation what can be applied to nodes conforming to SKWarpable protocol. It defines normalised vertex positions for source and destination where source positions are un-warped geometry and destination warped geometry. Therefore, if destination vertex positions are not equal to source, the node will look deformed.

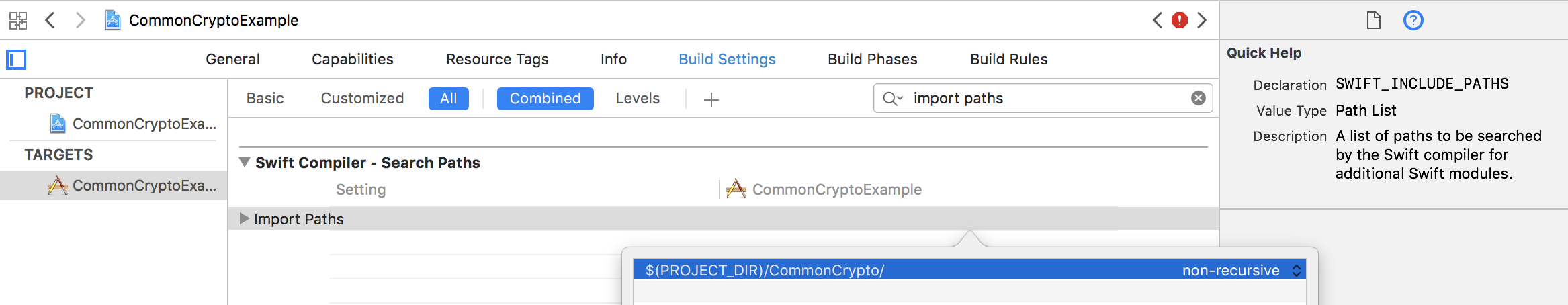

Vertex positions

Here is a geometry grid with 4 columns and 4 rows. Positions in grid are normalised and in case of un-warped geometry both x and y-values are in range of 0 to 1. Therefore, position at the top left corner has coordinates 0,1 and the bottom right 1,0. It should be noted that when deforming a node, destination vertex positions can have x and y values larger than 1 and less than 0 – node will just look stretched.

Deforming a node

Deforming a sprite consists of two steps: creating a SKWarpGeometryGrid and applying it to a warpable node. Firstly, let’s create a function on SKWarpGeometryGrid what takes in a normalised contact position and returns a deformed grid. Normalised means that the contact point is in grid’s coordinate system.

| extension SKWarpGeometryGrid { | |

| func deform(at contactPoint: float2, radius: Float) -> SKWarpGeometryGrid { | |

| // Make a copy of current grid positions. | |

| let currentPositions: [float2] = { | |

| var positions = [float2](repeating: .zero, count: vertexCount) | |

| (0..<vertexCount).forEach({ positions[$0] = destPosition(at: $0) }) | |

| return positions | |

| }() | |

| // Move some of the positions in the grid close to contact point. | |

| let destination = currentPositions.map { (gridPoint) -> float2 in | |

| let contactDistance = gridPoint.distance(to: contactPoint) | |

| guard contactDistance <= Float(radius) else { return gridPoint } | |

| // If contact was very close to the grid point, move it a little bit further away from the contact point. | |

| let gridPointChangeFactor = (Float(radius) - contactDistance) / Float(radius) | |

| let maxDeformation: Float = 0.1 | |

| let gridPointDistanceChange = Float(maxDeformation) * gridPointChangeFactor // vector length | |

| // Limit angle, as otherwise the edges of the crater are too far away from the center of the node. | |

| let angleToCenter = contactPoint.angle(to: float2(x: 0.5, y: 0.5)) | |

| let maxAngleOffset = Float.pi / 4.0 | |

| let minAngle = angleToCenter - maxAngleOffset | |

| let maxAngle = angleToCenter + maxAngleOffset | |

| var gridPointOffsetAngle = contactPoint.angle(to: gridPoint) | |

| gridPointOffsetAngle = min(max(gridPointOffsetAngle, minAngle), maxAngle) | |

| return float2(x: gridPoint.x + gridPointDistanceChange * cos(gridPointOffsetAngle), y: gridPoint.y + gridPointDistanceChange * sin(gridPointOffsetAngle)) | |

| } | |

| return replacingByDestinationPositions(positions: destination) | |

| } | |

| } |

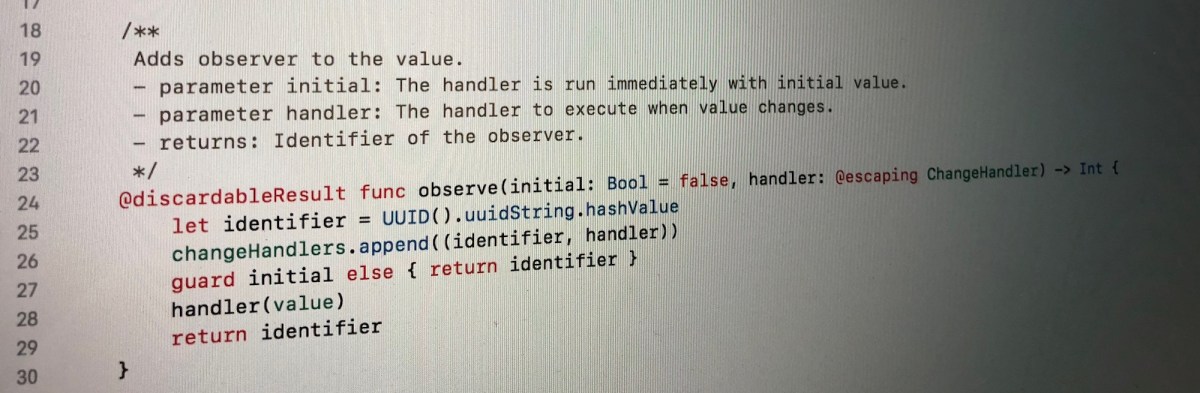

This function copies all the current destination vertex positions as node might be already deformed. Secondly, it loops over all the vertex positions and modifies the ones, which are fairly close to the contact point. The amount how much each vertex position is moved should depend on the distance to the contact point. The angle is calculated between the contact point and the grid position. Angle is clamped for avoiding moving vertex positions too far away from the centre point what gives more natural deformation. Magnitude and angle gives us a deformation vector for a given vertex position.

Here we can see a contact point in green and moved vertex positions. In one case, angle is not limited and vertex position is moved further away (contact point, old vertex position and new vertex position line up). In the second case, angle of the offset vector is clamped and the vertex position moves to the right and it will not line up with the contact point and previous position.

The deformed geometry can be applied by setting warpGeometry property which will deform the node without an animation. For animating deformation, use warp(to:duration:).

| func touchUp(atPoint position: CGPoint) { | |

| let gridContactPoint = position.normalizedContactPoint(sprite.position, rotation: sprite.zRotation) | |

| let grid = sprite.warpGeometry as? SKWarpGeometryGrid ?? SKWarpGeometryGrid(columns: 4, rows: 4) | |

| let deformedGrid = grid.deform(at: float2(Float(gridContactPoint.x), Float(gridContactPoint.y))) | |

| guard let action = SKAction.warp(to: deformedGrid, duration: 0.5) else { fatalError("Invalid deformation.") } | |

| action.timingMode = .easeOut | |

| sprite.run(action, withKey: "deform") | |

| } |

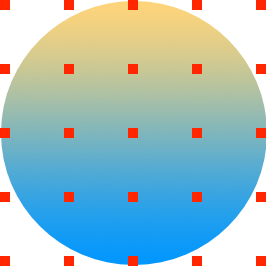

Finally, here is a demo app with a rotating circle and clicking anywhere around the circle will cause it to deform.

Summary

SKWarpGeometryGrid adds a simple way for creating deformations in SpriteKit. The precision of the deformation is defined by the amount of vertex positions in a grid. Applying coordinate system transformations and using euclidian geometry, it is possible to create pretty cool deformations with a little bit of code.

Playground

SKWarpGeometryGridExample (GitHub) Xcode 10, Swift 4.2

References

SKWarpGeometryGrid (Apple)

SKWarpable (Apple)

Euclidian geometry (Wikipedia)