I have written before about running tests and getting code coverage data for Swift packages in Running tests in Swift package with GitHub actions and Code coverage for Swift Packages with Fastlane. In this post, I am going to revisit the problem and use only tools from Xcode: xcodebuild and xccov. One downside of the approach in Code coverage for Swift Packages with Fastlane is that it required to generate Xcode project which is a deprecated feature in Xcode 12.5, and also it used xcov for forcing code coverage which does not seem to be maintained. Therefore, take two is here. I have a tiny Swift package on GitHub called IndexedDataStore, and we’ll add min code coverage requirement with GitHub action to that package.

Generating xcresult bundle with code coverage information

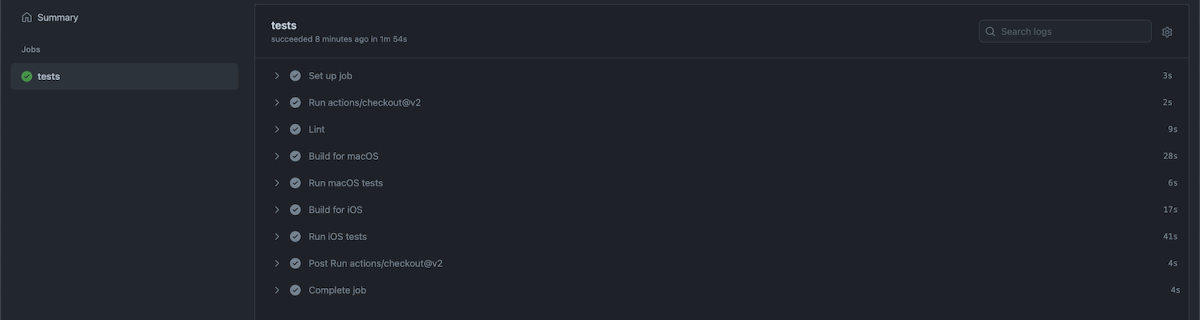

IndexedDataStore Swift package already has a GitHub action set up which runs tests for macOS and iOS platforms. As we’ll need to run several commands, then we’ll add a new ci-ios-code-coverage.sh script to Scripts folder and then the GitHub action will just invoke that script. This allows to run the same commands easily in the local development environment. Let’s take a look at the first half of the script, which builds and runs tests and generates a result bundle with code coverage information.

The pre-clean section of the script makes sure that we do not have files present. The RESULT_BUNDLE is created by xcodebuild and RESULT_JSON later when processing the bundle. Although we could skip deleting the RESULT_JSON then on the other hand RESULT_BUNDLE must always be deleted or otherwise xcodebuild will log a warning and wouldn’t create a new one. The run tests section is separated into two steps: build the package for testing and then running tests without building. An alternative would be to use test argument instead of build-for-testing and test-without-building. The current setup makes it easier to see which step failed: was it a build error or a test error. Code coverage is enabled by passing enableCodeCoverage=YES and specifying a path where the result bundle should be created with resultBundlePath. Other things to note is that we are using set -o pipefail for making sure the script wouldn’t ignore any errors and would fail immediately. Also, we’ll pipe xcodebuild’s output to xcpretty for a bit nicer output in logs. If we run this piece of script then we end up with a CodeCoverage.xcbundle which contains code coverage information in the package root.

Extracting line coverage and forcing min coverage

For extracting code coverage information from the CodeCoverage.xcresult bundle we can use Apple’s xccov command line tool which was built exactly for that. The first step is that we’ll convert CodeCoverage.xcresult to CodeCoverage.json file with xccov.

The second step is to parse the create json file which lists all the targets and their code coverage. I am not fully sure why, but it contains two targets with the same name IndexedDataStore. One target contains correct code coverage, but the other one is just an empty target but with the same name. Therefore we’ll need to filter out the empty one which luckily is not so difficult with jq command line tool. The jq command first takes an array for key targets and then finds a target which has a name “IndexedDataStore” and value for key executableLines is greater than 0. After that, we can access the key lineCoverage in the found target. Finally, we’ll convert the code coverage to percentages, but as the value is in float then we’ll need to use the bc command.

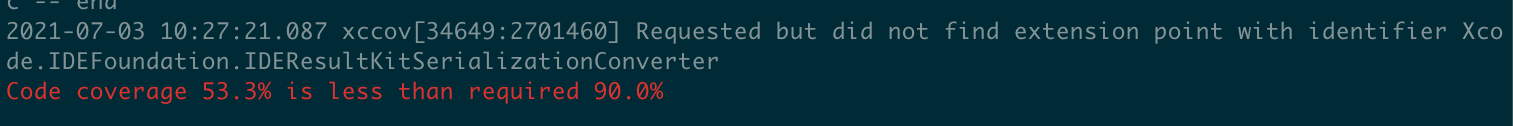

After extracting the code coverage, we can proceed with forcing a minimum code coverage. Yet again, we’ll use bc command when comparing two float values and then checking if the comparison was true. If code coverage is too low, we’ll print red error message and in case it was enough, we’ll print success message in green colour.

Calling the script from GitHub action

The created script can now be called from a GitHub action.

Summary

In this blog post we revisited code coverage set up for Swift packages. By using xcodebuild and xccov we created code coverage setup for Swift packages.

If this was helpful, please let me know on Mastodon@toomasvahter or Twitter @toomasvahter. Feel free to subscribe to RSS feed. Thank you for reading.