A while ago I wrote about using MVVM in a SwiftUI project. During the WWDC’20 Apple announced @StateObject property wrapper which is a nice addition in the context of MVVM. @StateObject makes sure that only one instance is created per a view structure. This enables us to use @StateObject property wrappers for class type view models which eliminates the need of managing the view model’s lifecycle ourselves.

Comparing @StateObject and @ObservableObject for view model property

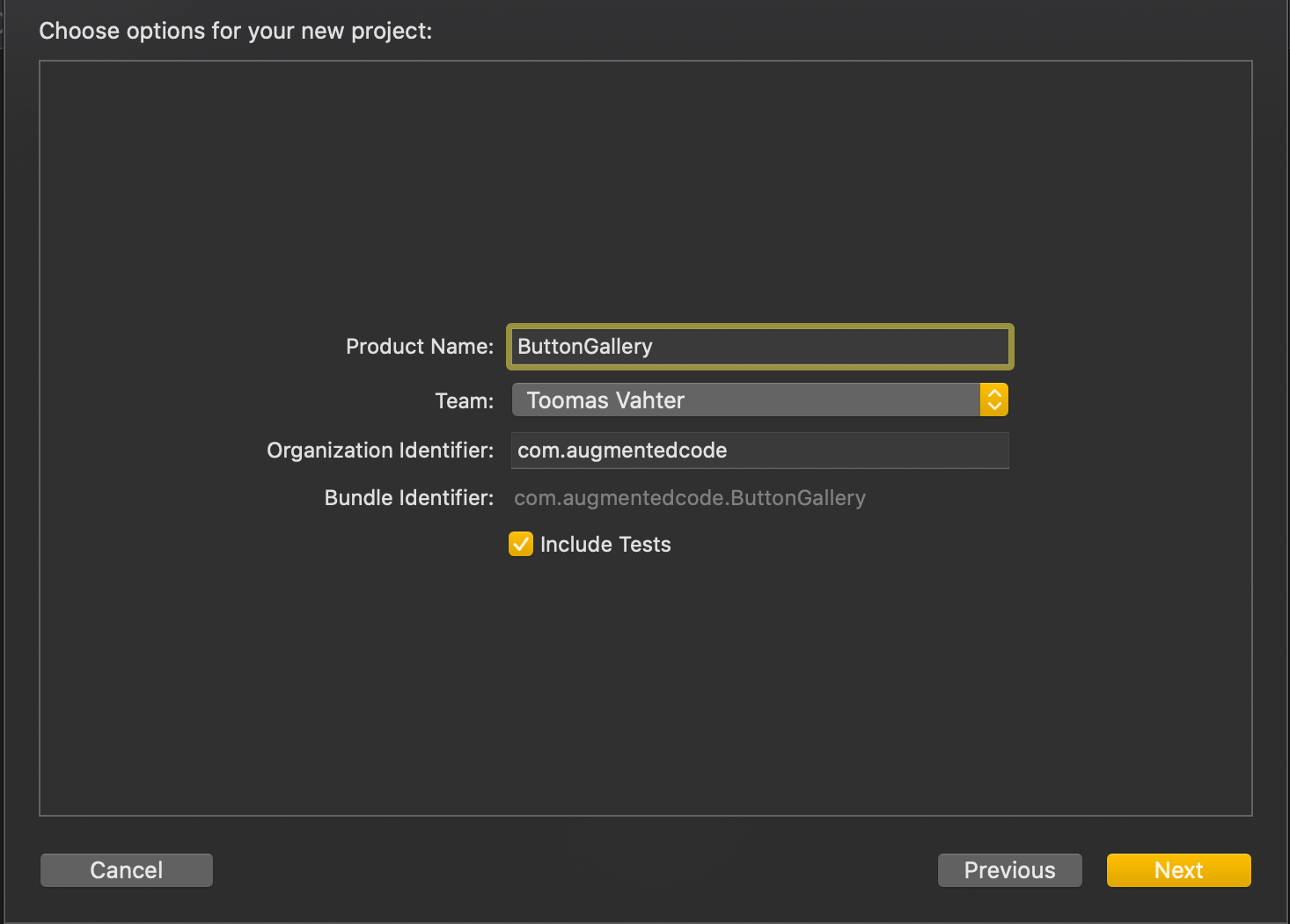

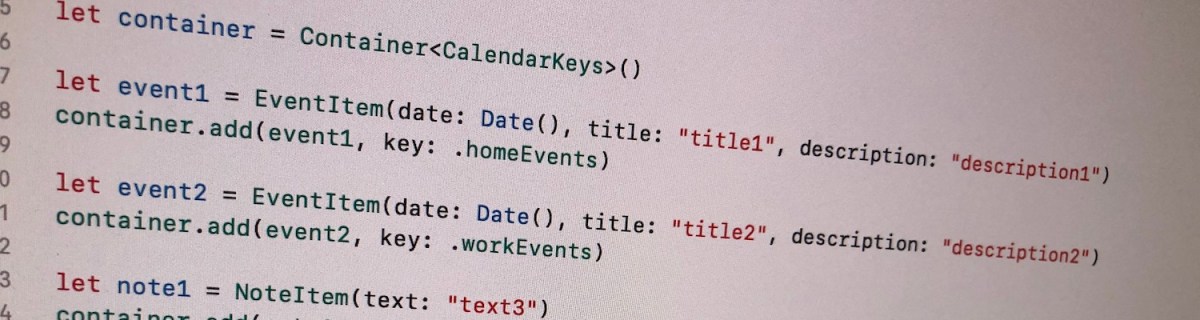

The most common flow in MVVM is creating and configuring a view model, which includes injecting dependencies, and then passing it into a view. This creates a question in SwiftUI: how to manage the lifecycle of the view model when view hierarchy renders and view structs are recreated. @StateObject property wrapper is going to solve this question in a nice and concise way. Let’s consider an example code.

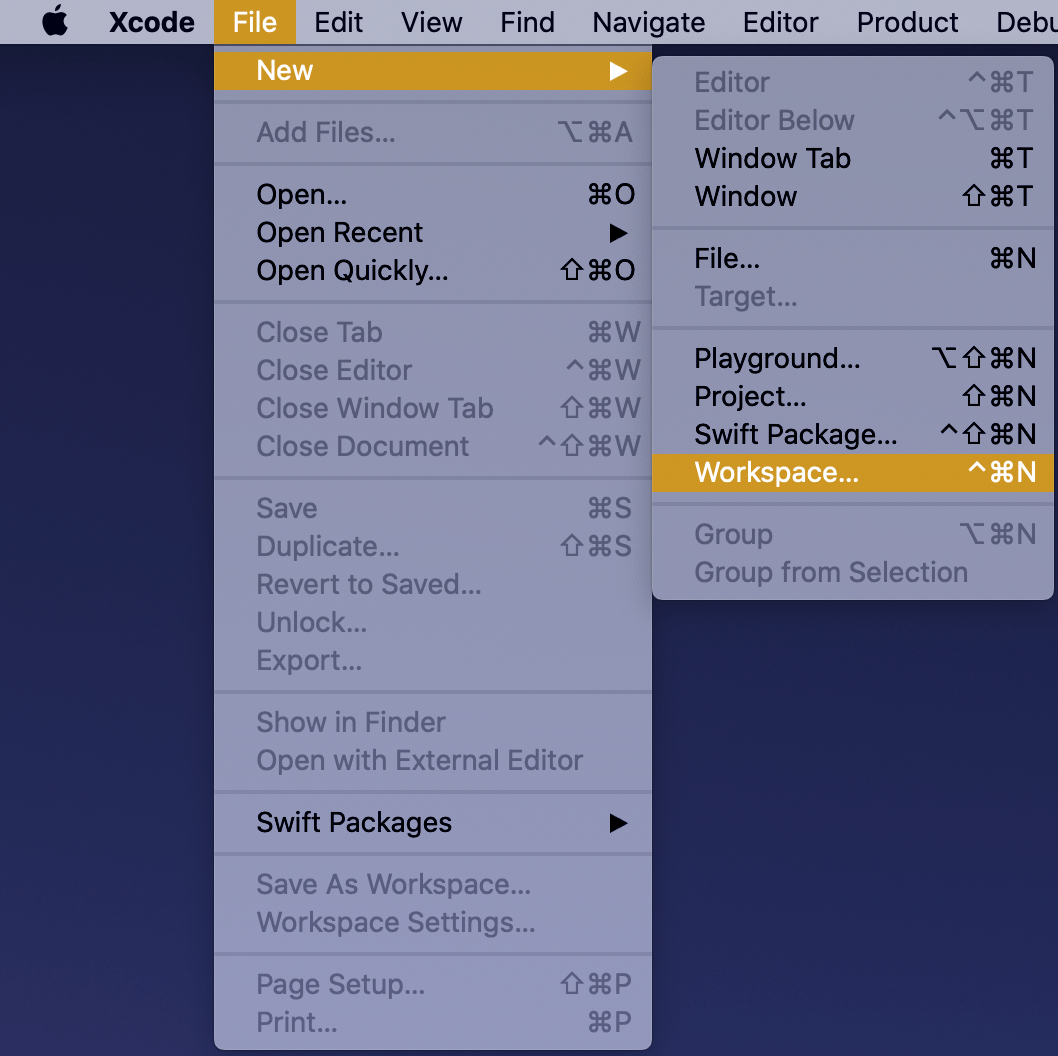

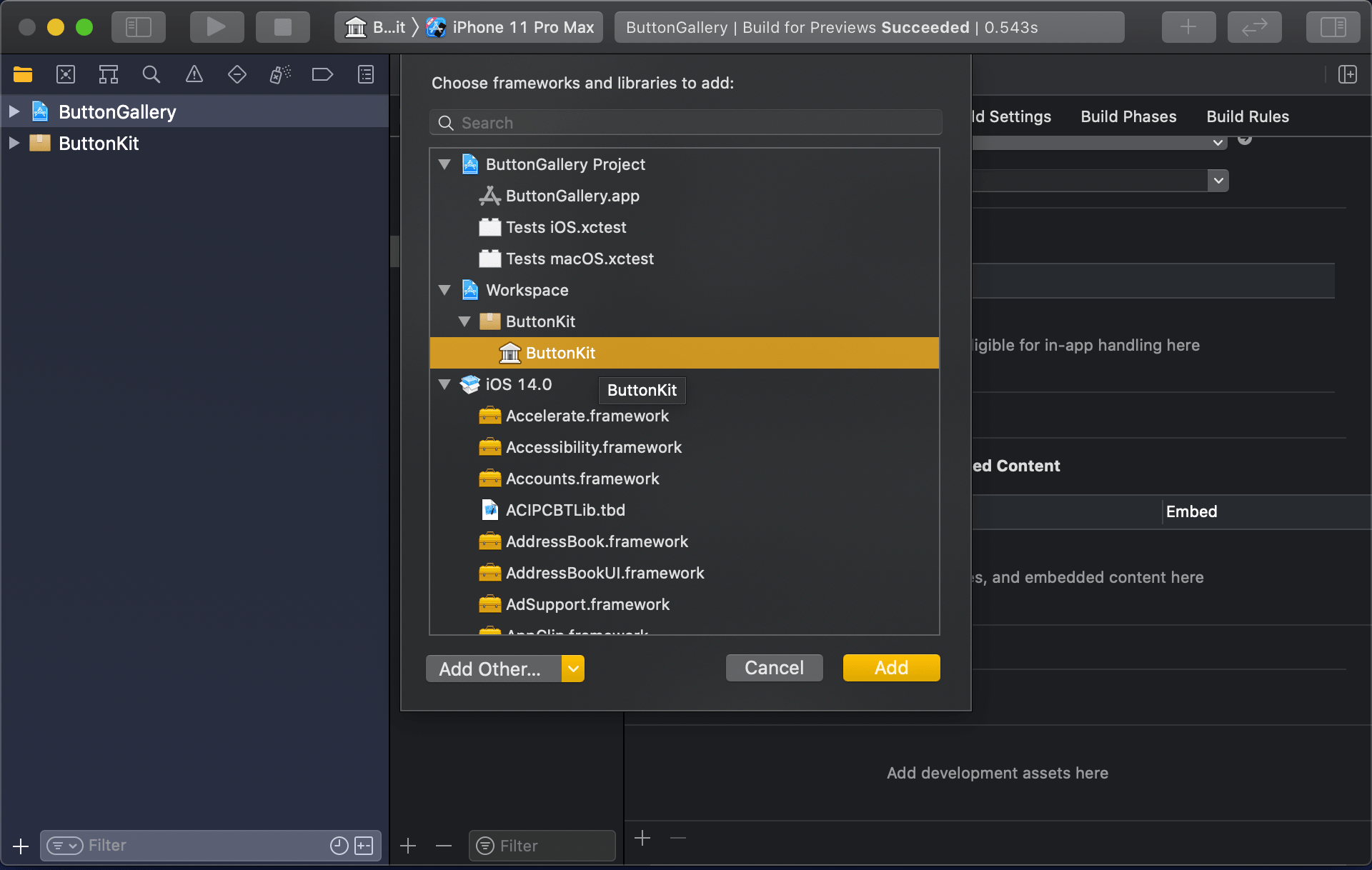

ContentView is a simple view which has a view model managing the view state and DependencyContainer used for injecting a dependency to the BottomBarViewModel when it is created. As we can see, ContentView’s view model is managed by @StateObject property wrapper. This means that ContentViewModel is created once although ContentView can be recreated several times. BottomBarView has a little bit more complex setup where the view model requires external dependency managed by the DependencyContainer. Therefore, we’ll need to create the view model with a dependency and then initialize BottomBarView with it. BottomBarView’s view model property is also annotated with @StateObject property wrapper.

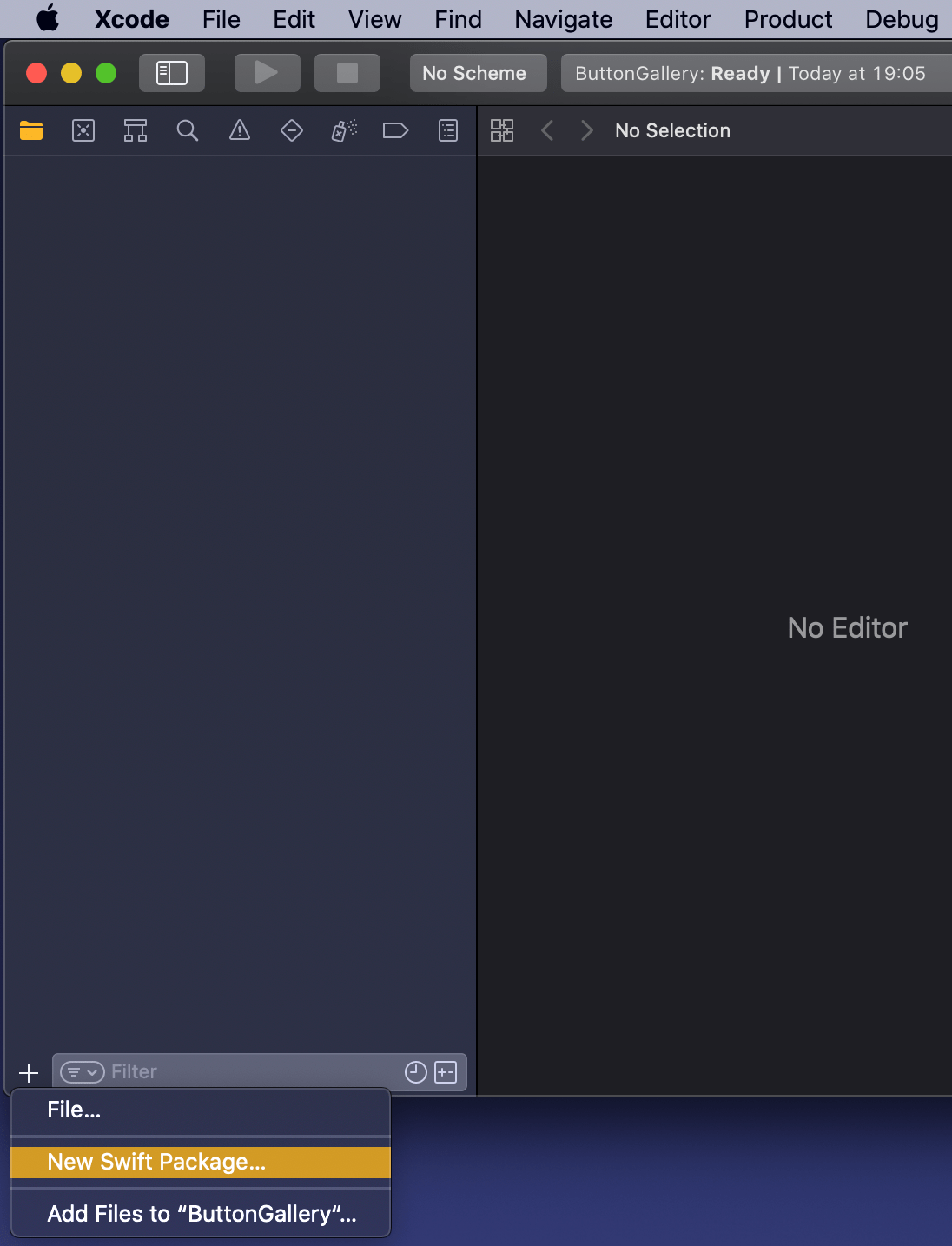

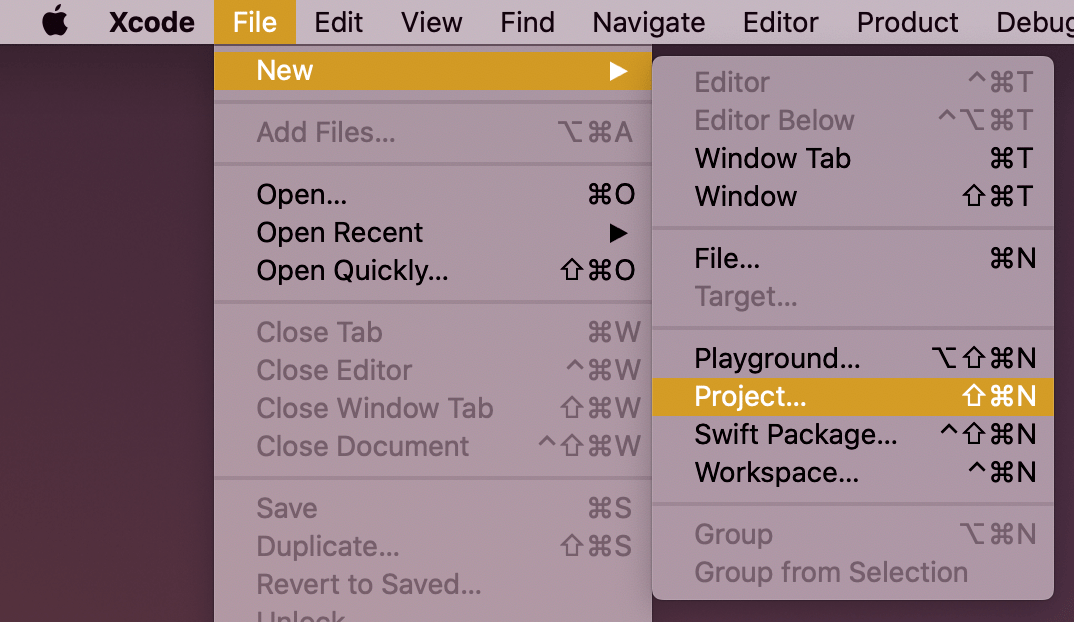

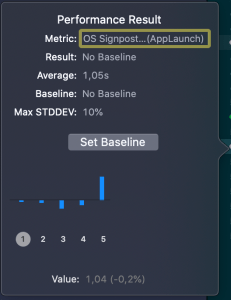

Magical aspect here is that when the ContentView’s body is accessed multiple times then BottomBarViewModel is not recreated when the BottomBarView struct is initialized. Exactly what we need – view will manage the lifecycle of its view model. This can be verified by adding a print to view model initializers and logging when ContentView’s body is accessed. Here is example log which compares BottomBarView’s view model property when it is annotated with @StateObject or @ObservableObject. Note how view model is not created multiple times when BottomBarView uses @StateObject.

BottomBarView uses @StateObject for its view model property

SwiftUIStateObject.ContentViewModel init()

1 ContentView.body accessed

SwiftUIStateObject.BottomBarViewModel init(entryStore:)

Triggering ContentView refresh

2 ContentView.body accessed

Triggering ContentView refresh

3 ContentView.body accessed

BottomBarView uses @ObservableObject for its view model property

SwiftUIStateObject.ContentViewModel init()

1 ContentView.body accessed

SwiftUIStateObject.BottomBarViewModel init(entryStore:)

Triggering ContentView refresh

2 ContentView.body accessed

SwiftUIStateObject.BottomBarViewModel init(entryStore:)

Triggering ContentView refresh

3 ContentView.body accessed

SwiftUIStateObject.BottomBarViewModel init(entryStore:)

Summary

WWDC’20 brought us @StateObject which simplifies handling view model’s lifecycle in apps using MVVM design pattern.

If you are looking more information about the MVVM design pattern then please check: MVVM in SwiftUI and MVVM and @dynamicMemberLookup in Swift.

If this was helpful, please let me know on Mastodon@toomasvahter or Twitter @toomasvahter. Feel free to subscribe to RSS feed. Thank you for reading.

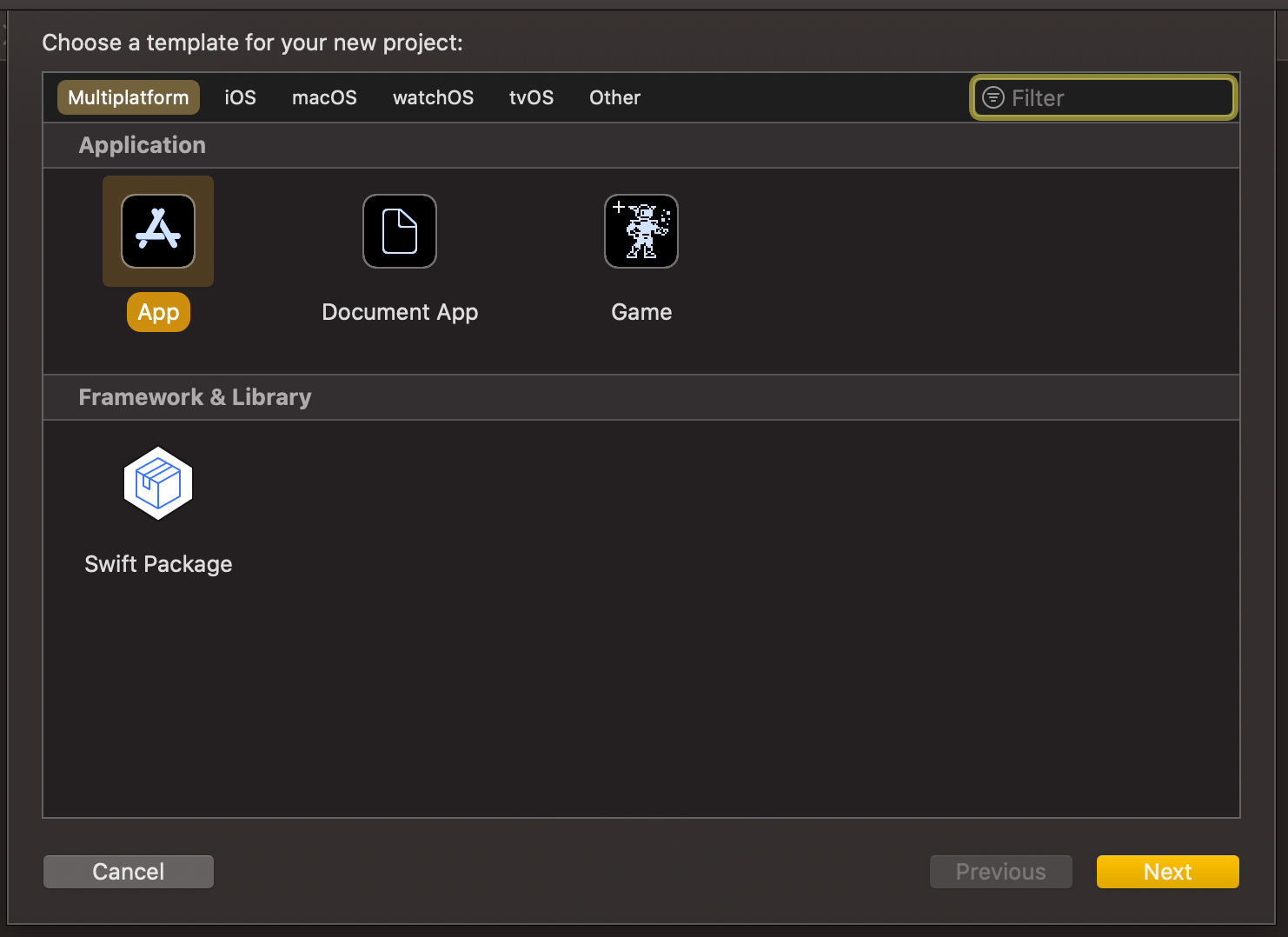

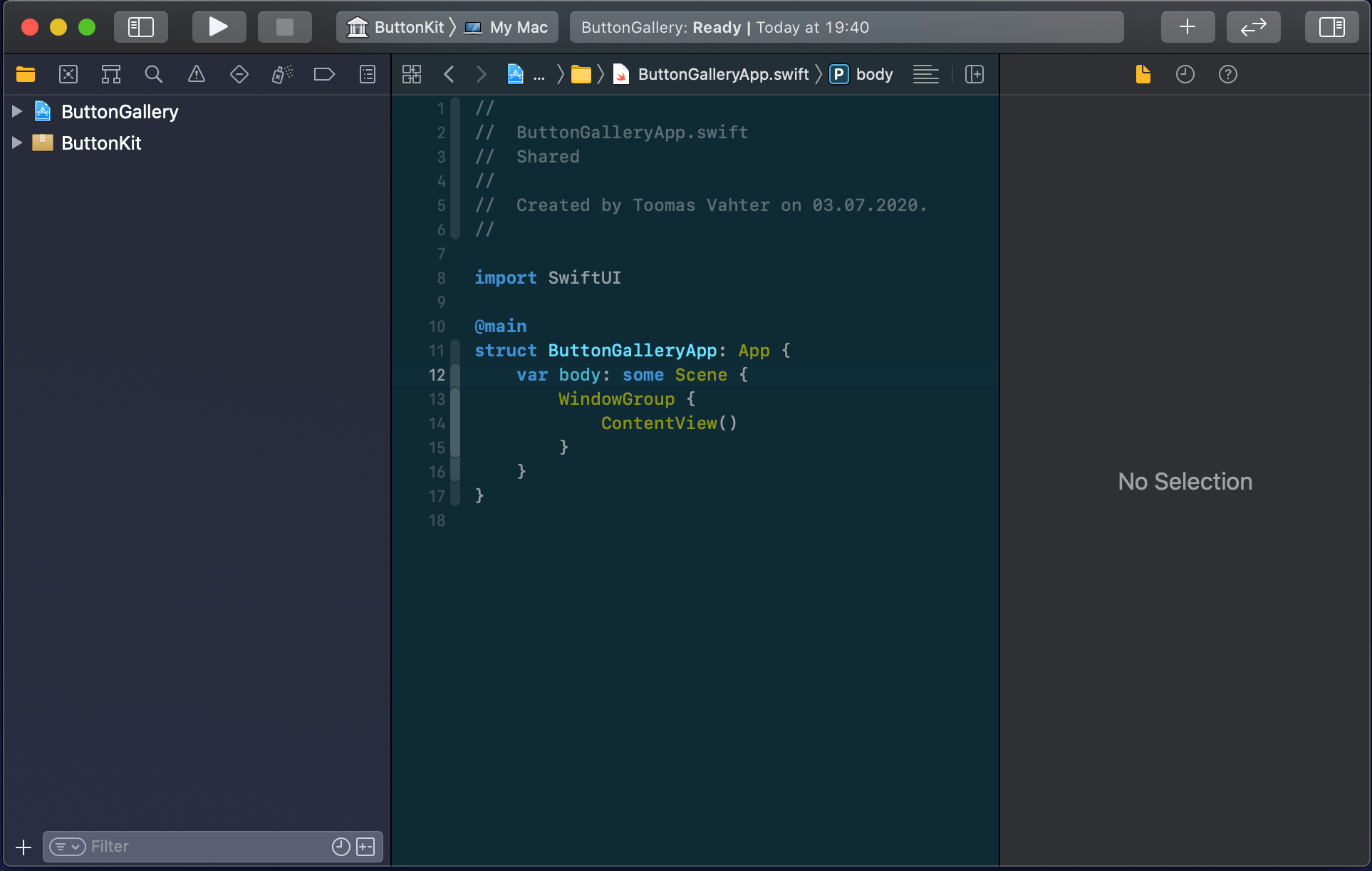

Example

SwiftUIStateObject (GitHub) Xcode 12.0 beta 3